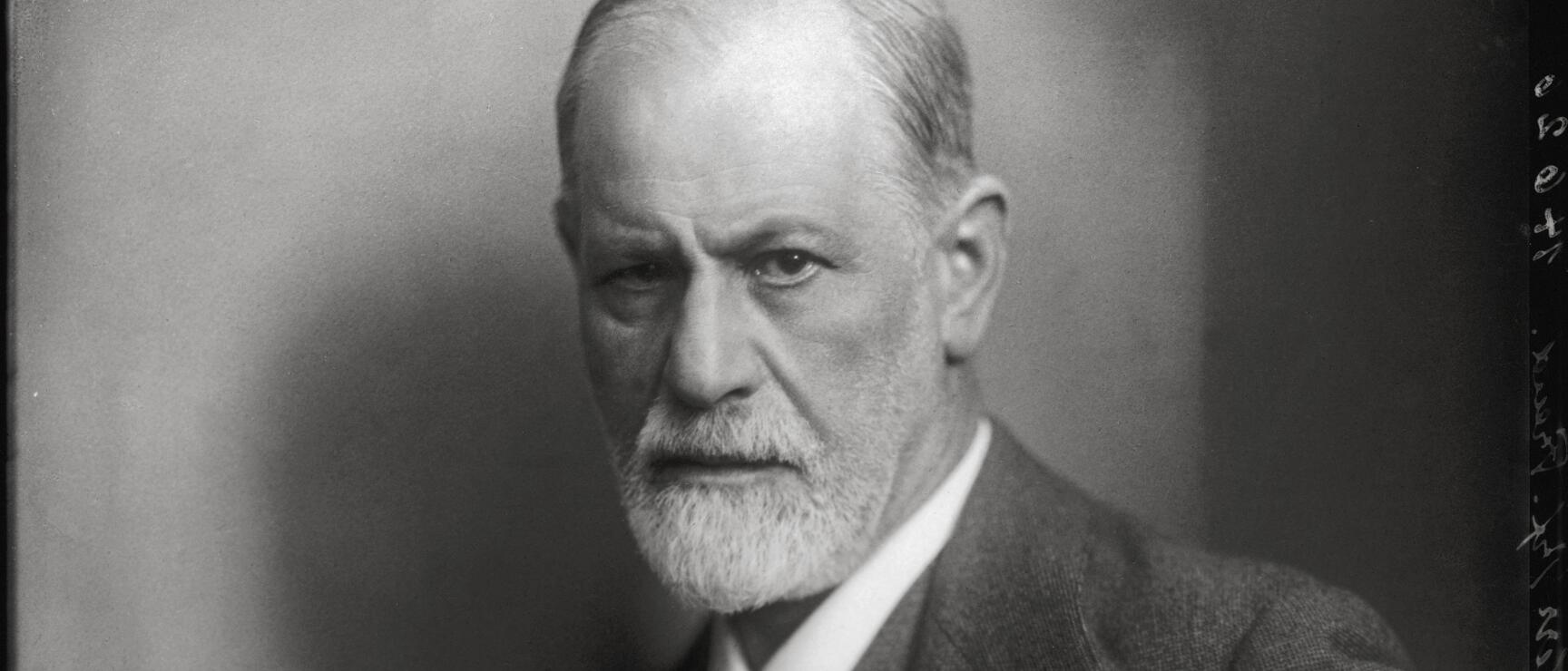

Sigmund Freud

Father of psychoanalysis – between everyday life in Vienna, the couch and cultural history

Sigmund Freud was born in 1856 in Freiberg in Moravia. In 1859, he moved with his family to Vienna, a city that would profoundly shape his thinking. After attending secondary school, he studied medicine at the University of Vienna, received his doctorate in 1881 and worked as a physician at Vienna General Hospital.

A study stay in Paris in 1885 with Jean-Martin Charcot marked a turning point in Freud’s understanding of illness and the human psyche. Back in Vienna, he set up his own medical practice and began to explore new approaches to understanding the mind. As early as 1882, he had secretly become engaged to Martha Bernays. As Freud was not yet financially secure and Martha had no dowry, the couple had to wait several years before marrying. Their long engagement became an intense long-distance relationship, sustained largely through letters. More than a thousand of these letters have survived, offering insight into Freud’s personal thoughts. Together, they had six children, including Anna Freud, who later gained international recognition and further developed her father’s work.

For almost five decades, Freud lived and worked at Berggasse 19 in Vienna’s 9th district. This address became the centre of his intellectual world. Here, he wrote key works such as The Interpretation of Dreams, published around 1900, which presented dreams as a gateway to the unconscious. The couch on which his patients lay became a symbol of psychoanalysis and the method of free association. Freud’s theories attracted international attention but also strong opposition, particularly because of his emphasis on sexuality as a fundamental psychological drive. Despite this, his work gained recognition: in 1902 he was appointed associate professor, and in 1919 full titular professor at the University of Vienna. In 1924, the City of Vienna made him an honorary citizen, and in 1930 he received the Goethe Prize of the City of Frankfurt.

In 1938, persecution by the National Socialist regime forced Sigmund Freud to emigrate to London, where he died on 23 September 1939. His work continues to influence far more than medicine alone. Literature, art, film and philosophy still draw on the ideas of the founder of psychoanalysis. The foundations of this legacy were laid in Vienna – a city where science, everyday life and culture remain closely intertwined.

On the Bellevuehöhe in the Vienna Woods, Freud had the decisive insight for his theory of dream interpretation in 1895.

Meet Sigmund Freud

‘Let the biographers struggle – we do not want to make it too easy for them. Everyone will believe their own view of the “development of the hero” to be correct, and I already look forward to how mistaken they will be.’

Letter to his wife Mrs. Martha Bernays

Tracing Freud in Austria

Sigmund Freud Museum Vienna

A doorbell, a staircase, a doorway: a visit to the Freud Museum Vienna begins exactly where Sigmund Freud once received his guests. He lived and worked at Berggasse 19 for almost 50 years, developing his ideas while balancing family life, research and the city around him. Today, the original rooms offer insight into this everyday world. Since the renovation in 2020, all areas are accessible for the first time, from the waiting room to the private living quarters.

Photographs, objects and personal traces tell the story of Freud’s life and work and the development of his ideas on dream interpretation. Although the original couch is now in London, it can be virtually returned to its place via augmented reality. The museum is complemented by Europe’s largest psychoanalysis library, a research institute, and a programme of temporary exhibitions and contemporary art.